“Here on the Northwest Coast the red cedar is considered the tree of life,” says Campo. “It allowed the building of large societies, big structures, canoes for transportation, totems, clothing, household tools, containers, utensils … it’s the ever-giving gift for our people.”

Standing in ‘Ksan Historical Village in Hazelton in Northern BC, it’s easy to feel a connection to British Columbia’s spiritual heartbeat. With the junction of the mighty Skeena and Bulkley rivers frothing at your back, majestic Stegyawden mountain (a.k.a. Roche de Boule) towering over your shoulder, and a row of Gitxsan First Nations cedar longhouses in front of you the park resonates with beauty and visceral history. For centuries, possibly millennia, the site has served as an important Indigenous fishing ground and transportation hub.

But ‘Ksan, which also includes a collection of historic totem poles and a pristine campground, isn’t just a picture-perfect setting in which to connect with BC’s diverse First Nations past. It’s a place to interact with its present and look into a brilliant future.

“We’re seeing travel as a way to create a bigger understanding of Indigenous cultures all across the province,” says Paula Amos of Indigenous Tourism BC. “It’s especially good to watch all the youth who are wanting to revitalize their cultures.”

Images from ‘Ksan Historical Village in Hazelton: Photo: Grant Harder, Photo: Dannielle Hayes, Photo: Andrew Strain

Amos’ sentiment echoes throughout the province’s 203 First Nations—that’s about one-third of all Canada’s First Nations groups. An explosion of interest in Indigenous culture, history, art, and commerce has been propelled by recently signed treaties, more inclusive government policies, and a new generation of leaders committed to carving out a prominent and prosperous identity for First Nations. For the traveller this means almost-endless options for unique, immersive experiences.

Candace Campo, co-owner of Talaysay Tours, is one of many trailblazers across BC bringing life to Indigenous travel experiences. A member of the coastal Shíshálh (Sechelt) Nation, she leads tours around Vancouver; one of the more popular outings takes in the famed totem poles at Brockton Point. Amid the moss-draped forests and ancient monument cedars of Vancouver’s Stanley Park, it’s the province’s most visited and probably most photographed tourist attraction.

“Here on the Northwest Coast the red cedar is considered the tree of life,” says Campo. “It allowed the building of large societies, big structures, canoes for transportation, totems, clothing, household tools, containers, utensils … it’s the ever-giving gift for our people.”

Vancouver, British Columbia—on the Edge of Nature

Length -Diverse Land, Diverse People

Campo describes just one piece of a tapestry of cultures in the province, each with a history shaped by its own wild and natural gifts. Archaeologists and other scholars believe the Northwest Coast was likely one of the most densely populated areas of North America prior to European contact, with anywhere from 200,000 to more than 500,000 people in the mid-eighteenth century. Inhabiting the area now known as British Columbia for more than 10,000 years, approximately 200,000 Indigenous people—including First Nations, Inuit, and Métis—currently live in British Columbia. First Nations communities in BC are spread across six distinct regions.

Because the province includes ecosystems ranging from coastal to sub-arctic tundra to Rocky Mountains, it’s natural that each of the First Nations has developed its own culture—one for travellers to experience first hand.

Far from the coast and encompassing a territory that includes spectacular deserts, lakes, alpine forests, and grasslands, it’s little wonder the Syilx/Okanagan Peoples say: “We Are Beautiful, We Are Okanagan, Because Our Land is Beautiful.” Part of that beauty is exemplified at the Nk’Mip Desert Cultural Centre, where visitors can learn about the land along a network of walking paths and explore the rich living culture of the Osoyoos Indian Band with several interactive learning experiences and a reconstructed village.

Nk'Mip Desert Cultural Centre, Hubert Kang| First Nations pit house at the Nk'Mip Desert Cultural Centre, Andrew Strain | Teepees at the Nk'Mip Cultural Centre in BC's Okanagan Valley, Adrian Brijbassi

Locally known as Kliluk, the lake’s mineral deposits and surrounding ceremonial cairns have drawn comparisons to the lake shores at Columbus crater on Mars. More modern, and easily accessed, the gorgeous Quaaout Lodge & Spa at Talking Rock Golf Resort provides a luxury experience (and superb local wine list) amid unforgettable Thompson Okanagan grandeur.

Interior cultures—which tended to follow migrating food sources as opposed to living near reliable fishing areas around the coast and rivers—often more resemble Indigenous nations of the Canadian and American plains. Powwow culture, for example, has become a major component of social gatherings. An unforgettable experience, the province’s biggest powwow—with nearly 1,000 dancers in magnificent ceremonial dress—is the annual Kamloopa Powwow, held in Kamloops in early August. Visitors are welcome.

Scenes from the Kamloopa Powwow: Photos top row and bottom two left: @nathanielatakora, Photo bottom right: @xshaydx

Like others, Lucy Martin, an Indigenous Tourism Specialist in Northern BC, speaks enthusiastically of a “younger generation eager to share their stories.” One of her favourite examples is a traditional pit house, different in construction from cedar longhouses found in other parts of the province. Students from the University of Northern British Columbia and high school students from the Lheidli T’enneh First Nation around Prince George built it in 2014. A traditional winter dwelling dug four feet into the ground, the UNBC Pit House is constructed with earthen walls and wooden beams in the style of the Dakelh, an Indigenous people from north-central British Columbia.

Unique adventures and physical challenges are naturally a big part of First Nations travel offerings. Hidden just off BC Highway 1 and spectacularly sited amid diverse mountain ranges at the roaring confluence of the mighty Fraser and Thompson rivers, the Village of Lytton is located on the gathering site of Nlaka’pamux Village where First Nations people have made their home for 10,000 years.

The area population of approximately 2,000 includes neighbouring Lytton First Nation, Skuppah, Nicomen, Siska, and Kanaka bands. Outdoor activities include whitewater rafting, single-track mountain biking, and hiking in the majestic Stein Valley Nlaka’pamux Heritage Park. Here visitors will find the ancient “birthing rock.” At this easy-to-access spot near a trailhead, women would line the stone ledges with soft fir boughs and give birth to their children in a sacred place.

Given the incredible diversity of Indigenous communities in the province, museums and associated tours make an introduction to it all simple.

In Northern BC, the Nisga’a Nation’s designated auto tour takes in 18 points of cultural interest (including historic villages) on a stretch of road jammed with world-class alpine scenery along Highway 113 that hugs the Nass River. Here, the Nisga’a Museum offers insight into an often-overlooked piece of history.

No one knows who carved the first totem pole. But the distinctive art popularly associated with Northwest Coast Indigenous cultures likely began with groups inhabiting the Nass Valley, a 240-kilometre (149-mile) drive inland from the port city of Prince Rupert. “They say pole carving developed in this area and spread to the Haida along the coast and all on to our neighbour Tsimshian and up north to the Tlingits in Alaska and all over,” says Eric Grandison, communications director of Gitlaxt’aamiks, the village that houses First Nation offices for the roughly 2,500 Nisga’a who live in the Nass Valley.

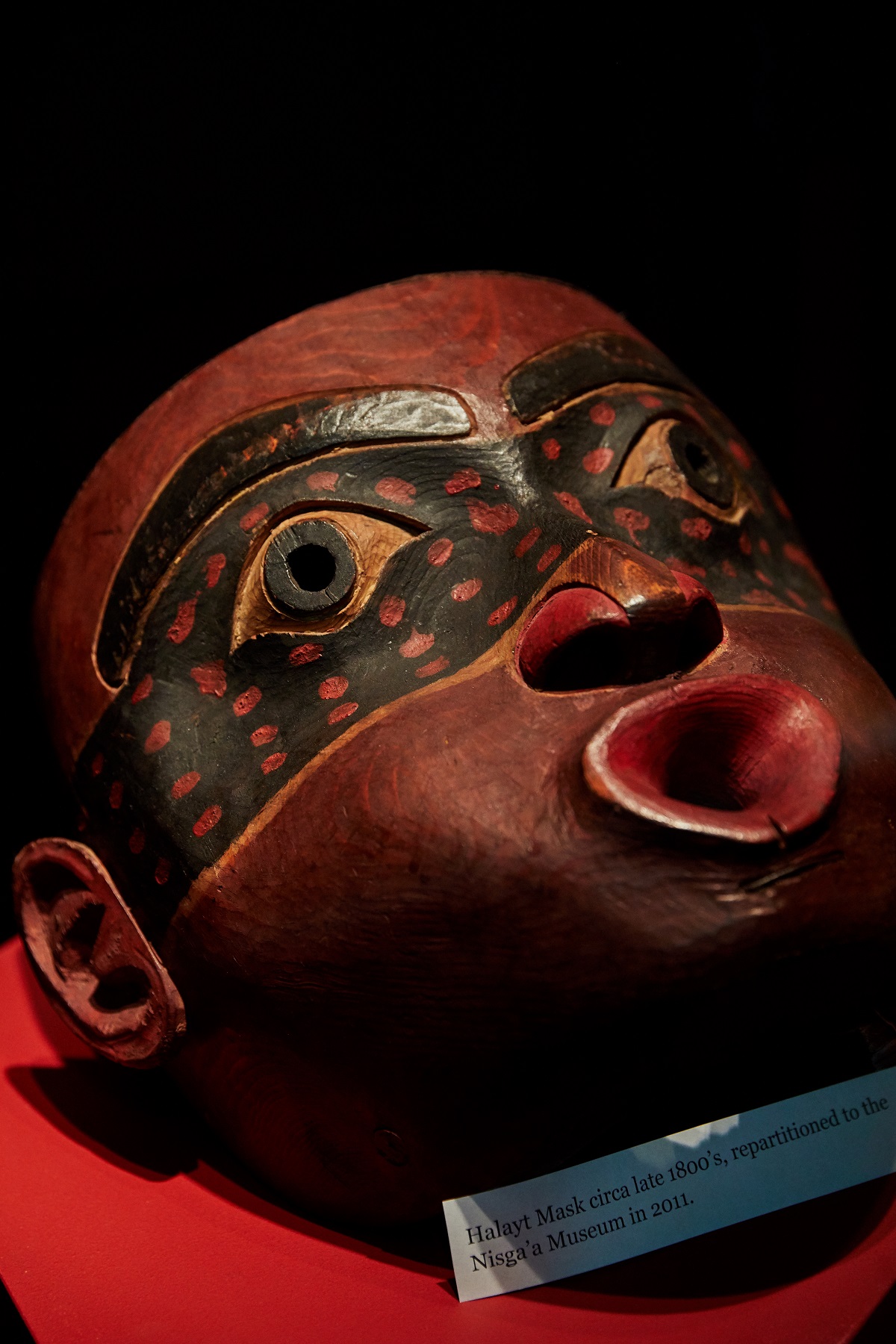

The Gitmaxmak'ay Nisga'a Dancers and the Wii Gisigwilgwelk (Big Northern Lights) Dancers at the Cassiar Cannery in Port Edward, Dave Silver | A mask from the Nisga’a Museum, Mike Seehagel | Totems outside the Nisga'a Museum | Mike Seehagel

A well-preserved, 30-foot totem pole from 1879 commands the entry of the $14 million Nisga’a Museum—opened in 2011, the magnificent structure pops up like a spaceship on the fringes of the Great Bear Rainforest. Like the pole, the museum’s entire collection consists of objects confiscated from the 1880s onward and repatriated in recent years per the landmark Nisga’a Treaty, signed in 2000 after 113 years of negotiation with the Canadian government.

“It’s an emotional piece for us here in the valley,” says museum director Stephanie Halapija of the totem pole. “The whole museum is a statement of survival. It’s very much ‘look what we’ve done. Despite everything, we’ve survived. We’re here.’”

“The whole museum is a statement of survival. It’s very much 'look what we’ve done. Despite everything, we’ve survived. We’re here.’”

See what's happening now with these recent posts.

Start Planning Your BC Experience

Getting Here & Around

Visitors to British Columbia can arrive by air, road, rail, or ferry.

Visit TodayAccommodations

Five-star hotels, quaint B&Bs, rustic campgrounds, and everything in between.

Rest Your Head

Subscribe to our newsletter